Support the Timberjay by making a donation.

The search for a cure for Soudan’s endangered bats

Researchers hoping to test possible treatments by this fall

SOUDAN— Despite the apparent deaths of hundreds of bats at the Soudan Mine from the effects of white-nose syndrome this winter, state park officials here remain hopeful that the kind of mass …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Attention subscribers

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, or purchase a new subscription.

If you are a current print subscriber, you can set up a free website account and connect your subscription to it by clicking here.

If you are a digital subscriber with an active, online-only subscription then you already have an account here. Just reset your password if you've not yet logged in to your account on this new site.

Otherwise, click here to view your options for subscribing.

Please log in to continue |

The search for a cure for Soudan’s endangered bats

Researchers hoping to test possible treatments by this fall

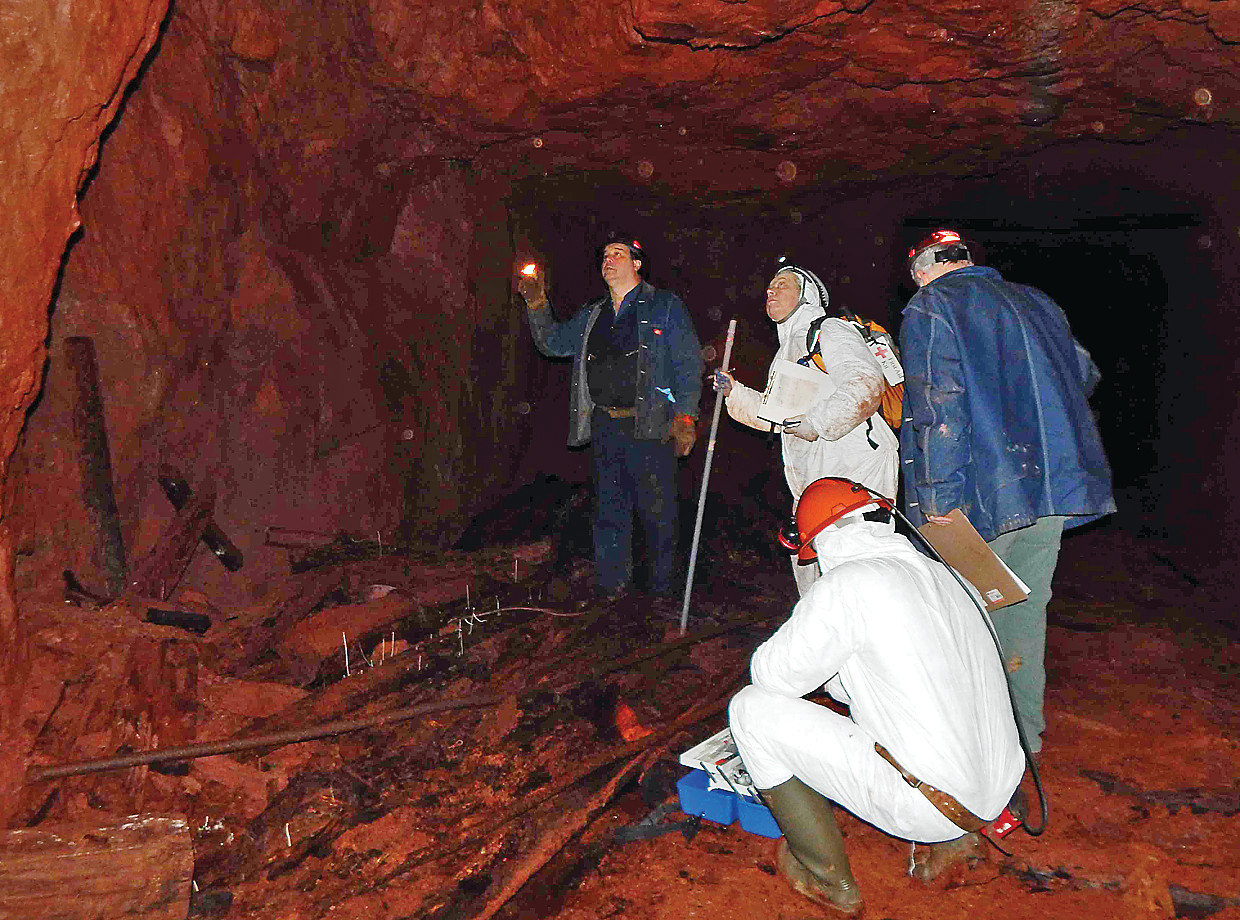

SOUDAN— Despite the apparent deaths of hundreds of bats at the Soudan Mine from the effects of white-nose syndrome this winter, state park officials here remain hopeful that the kind of mass die-off experienced at other major bat hibernacula elsewhere in the U.S. may still be avoided.

That’s because of promising developments at the University of Minnesota, where researchers are finding some success in identifying microbes found naturally in the mine that may be able to slow or halt the development of the fungus that causes the syndrome. With luck, researchers hope to begin field trials as early as this fall.

While the loss of bats this winter was significant, researchers found most bats still alive and hibernating peacefully during an annual population survey conducted in the mine in February. “We really did not witness mortality underground,” said Jim Essig, manager of the Lake Vermilion Soudan Underground Mine State Park. Park officials had, however, noticed hundreds of bats leaving the mine this past January, an exodus apparently prompted by the growth of white-nose syndrome among bats in some parts of the mine. The syndrome does not kill bats directly, but irritates them enough to force them out of hibernation, often at times of the year when the bats can’t find food or water. The bats that emerged in January during a cold snap quickly died in temperatures that were well below zero.

The exodus of bats has slowed considerably since mid-winter, according to Essig and the February survey suggests the worst of the losses could be over, at least for this year.

And that could provide a window of opportunity for researchers to test varieties of bacteria and fungi that they’ve isolated from samples collected in the Soudan mine that appear to retard development of the fungus Psueudogymnoascus destructans, or Pd for short, which is believed to cause the syndrome.

It appears the fungus was accidentally introduced into the U.S. in the mid-2000s and it began to kill large numbers of bats in the eastern U.S. beginning in 2007. The fungus has been spreading westward ever since and first showed up in Minnesota in 2013. The bats that died this winter at Soudan were the first confirmed bat deaths in Minnesota from the fungus.

For Christine Salomon, a researcher at the Center for Drug Design at the University of Minnesota, it’s just the latest evidence that she’s in a race against time. Salomon, who has been working with microbes isolated from deep in the Soudan Mine for the past several years, recently shifted the focus of her research from drugs for humans to a treatment or cure for white-nose syndrome.

From her early work, Salomon has known for several years that dozens of the mine’s differing varieties of microbes have strong anti-fungal properties, and as news and concern about the fungus that causes white-nose syndrome grew, she recognized that some of her organisms could offer a way to treat the disease.

“Determining the effectiveness of a particular microbe comes down to a screening process,” said Salomon. First, she applies swabs of samples collected in the mine to petri dishes, to determine if they do, in fact, have anti-fungal properties.

Salomon then tests those that do inhibit fungal growth on a variety of surfaces likely found in the mine, including on bat carcasses, to see whether they can survive outside the lab. That research is currently underway in her lab, said Salomon. Once she’s identified microbes that can survive on iron ore, bats’ wings, or other such substrates, she’ll be ready to begin field trials. And even if they find some microbes that do well, she still has to determine how to apply the treatment and how long it might last.

At the same time, Salomon needs to ensure that the treatment doesn’t cause more problems than it solves. That’s one of the risks of biological pest control, said Salomon. “If we’re killing fungus, we want to be sure we aren’t also killing bats,” she said.

By isolating potential anti-fungal treatments from within bat hibernacula, it likely reduces the risk that the use of the treatment will cause unanticipated harm to bats themselves. “We didn’t want to bring in something from outside. You always have to balance the potential consequences and they aren’t always clear,” she said.

Salomon said she’ll be looking for help on that issue during a national conference on white-nose syndrome planned for June, in Colorado. “We’re hoping to identify people who can help us with those steps,” said Salomon.

Under normal circumstances, the kind of research that Salomon is doing could take a decade from lab studies to field trials. But time is one luxury that researchers don’t have when it comes to white-nose syndrome, which is why Salomon hopes to be treating bats in the field by this fall. “People are trying to be extra careful, but they’re also really desperate for a solution,” she said. “In dealing with this, you want to be very, very cautious. But the flip side is we’re running out of time.”