Support the Timberjay by making a donation.

Can Tower ambulance afford new staffing plan?

Director acknowledges budget surplus could drop significantly under paid on-call proposal

TOWER— Tower Ambulance Director Steve Altenburg insists the city’s ambulance service will continue to operate in the black even when the service shifts to a paid on-call staffing system, …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Attention subscribers

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, or purchase a new subscription.

If you are a current print subscriber, you can set up a free website account and connect your subscription to it by clicking here.

If you are a digital subscriber with an active, online-only subscription then you already have an account here. Just reset your password if you've not yet logged in to your account on this new site.

Otherwise, click here to view your options for subscribing.

Please log in to continue |

Can Tower ambulance afford new staffing plan?

Director acknowledges budget surplus could drop significantly under paid on-call proposal

TOWER— Tower Ambulance Director Steve Altenburg insists the city’s ambulance service will continue to operate in the black even when the service shifts to a paid on-call staffing system, beginning April 2.

But Altenburg acknowledged in an interview last week that the service’s current budget surplus is likely to diminish, possibly significantly, as a result of hiring the on-call staff, who will work 24-hours a day, Monday-Friday.

That’s consistent with previous reporting in the Timberjay, which had noted that the service’s current operating surplus could offset the high cost of implementing the paid on-call staffing plan. However, final budget numbers for the ambulance from 2017 show a drop in the service’s operating margins even before hiring the additional staff.

Last April, when the Tower City Council approved Altenburg’s staffing proposal, his report to the council had claimed that the new staffing system would actually increase the service’s net revenues. Altenburg now agrees that claim was in error, and that he should have claimed an increase in gross revenues, since costs of the program are likely to exceed any additional revenues. “I have never said we were going to profit more,” Altenburg said, even though he acknowledges that his original written proposal did, in fact, make that claim.

Altenburg argues that new staff will allow the Tower Ambulance to take more inter-hospital transfers, which generate substantially more revenue than emergency calls. He said the service averages about $600 for an emergency call, while a transfer brings in about $1,300 before subtracting expenses. An analysis of 2017 ambulance billing records by the Timberjay found an actual average of $1,217 per transfer. The ambulance service completed 72 transfers last year, and Altenburg projects that will increase to 150 under his staffing proposal.

Altenburg was, at times, confrontational in the interview, repeatedly accusing this reporter of misrepresenting his proposal or “twisting numbers.” Altenburg was also contradictory at times, sometimes acknowledging the on-call proposal will diminish current budget surpluses, at other times, going back to his previous claims that the plan would more than pay for itself.

Altenburg was also occasionally defensive. “As long as we’re not losing money, what business is it of yours,” he said, referring to this reporter. “As long as we’re not losing money, who cares? We’re a not-for-profit agency.”

While Altenburg dismissed the need for maintaining operating margins, he also acknowledged that the service will need to use those margins to cover an ongoing shortfall in the fund that pays for new ambulances. The service’s two operating ambulances, which date back to 2011 and 2012, are close to retirement age, he said. “Some of the margin is going to have to cover the cost of buying new ambulances, because there’s not anywhere near enough to buy new ones,” said Altenburg.

The ambulance purchase account is supposed to be funded by an annual subsidy from the townships, which was increased two years ago. Altenburg said the subsidy will need to go up again to cover the cost of upcoming vehicle purchases. The service is likely to need to purchase two ambulances over the next couple years, and Altenburg said he wants to add a third rig to the service as well, as back-up. Ambulances can run as much as $200,000 or more.

According to budget data provided by City Clerk Treasurer Linda Keith, the ambulance rig account contained $118,000 as of the end of 2017.

The ambulance service’s 2017 fund balance totaled $636,315, but that includes a $140,000 insurance settlement for the fire that destroyed the service’s storage garage several years ago. That money is allocated towards some kind of a new facility.

Potential shortfall

How much the service’s operating margins might fall under Altenburg’s paid on-call plan depends on a number of factors, including how many additional transfers the service can complete (which will affect revenues) and how well Altenburg has assessed the costs of the plan.

Altenburg projects that the service will accept more transfers with on-call staffing, projecting 150 transfers, up from the 72 transfers the service completed in 2017 under the old staffing model. That would generate an additional $101,000 using Altenburg’s estimate of $1,300 per transfer, or $95,000 based on the average of actual payments in 2017.

When Altenburg originally presented the plan to the council, it did not include the cost of travel, payroll taxes, or the expense of providing housing for staff while on-call. Altenburg does include those costs in an updated budget provided to the Timberjay, which pegs the cost of the proposal at $177,000.

Altenburg at times continues to argue that his plan actually makes money, but he reaches that conclusion by attributing all 150 projected transfers, and the revenue they would generate, to be a result of the new staffing model. His analysis fails to account for the fact that the service’s current volunteers completed 72 transfers in 2017, without paid on-call staffing.

Altenburg’s plan also assumes that the paid on-call staff would not qualify for overtime, which is at odds with the findings of some other area ambulance directors, whose research has concluded differently. Altenburg’s proposal calls for on-call staff to work 60-hour shifts, which would potentially require the service to pay 20 hours of overtime on every shift. If so, that would add an additional $23,000 annually to the cost of the plan, putting the total price tag at approximately $200,000.

After the Timberjay raised questions in January about the potential for overtime costs associated with the plan, Linda Keith sought an opinion from city attorney Andy Peterson on the issue. Based on Keith’s explanation of the working circumstances of the new staff, Peterson concluded that the staff would not be subject to overtime requirements for periods when they were only on-call. But as Keith noted in her explanation to Peterson, that decision hinged primarily on whether the workers would be required to reside at or near the hall while on call. “Are we correct that the ‘being at the hall requirement’ is what saves us from OT?,” Keith asked in her letter to Peterson. Peterson concurred.

But Keith never informed the attorney in her letter that the city was planning to rent living quarters for the on-call staff, since they otherwise were unlikely to be able to make it to the hall within the five or ten-minute response time required by the position. To be exempt from the federal Fair Labor Standards Act and its overtime provisions, on-call personnel must generally be able to remain at home and use their on-call time as they see fit. If they’re expected to remain on or near the employer’s premises, whether at a fire hall or assigned living quarters, the more likely they’ll be considered subject to the FSLA and overtime.

When questioned by email about the failure to inform the attorney about the living quarters, Altenburg reacted angrily: “DUDE SERIOUSLY?!? You would be absolutely right if you weren’t so completely wrong. Of course the house is an extension of the fire hall as it is being rented by the ambulance, however I dnt (sic) give a flying monkeys butt if some one wants to live out of their car in Zup’s parking lot.” Altenburg said the only requirement is that paid on-call staff be within a ten-minute response time of the ambulance hall and would not be required to utilize the housing. Altenburg is proposing to spend approximately $9,000 a year for the living quarters because three of the four individuals recently hired for the on-call positions live too far away to meet the ten-minute response time. Those individuals currently live in Chisholm, Babbitt, Embarrass, and Tower, so most would be unable to remain at home during their on-call hours.

Qualification for overtime for on-call service hinges on more than just housing arrangements. The more frequently on-call staff are required to do work assignments, and the more hours those assignments entail, also factor into whether overtime rules would apply. In the case of the city’s on-call staff, the service’s average call volume suggests that on-call workers would be required to complete potentially lengthy work assignments multiple times each shift. Numerous legal cases in this area of law, reviewed by the Timberjay, suggest that the working arrangement established by the city could well leave the city liable for overtime. Failure to pay it up front could leave the city forced to provide back pay to on-call staff, as well as any attorney’s fees the workers might incur in obtaining a favorable ruling.

Altenburg was dismissive of the issue during last week’s interview. “I’m going by what the actual lawyer said,” he responded.

The plan proposed by Altenburg would likely bring in some other sources of revenue, such as increased state and county Medicaid subsidies provided for transporting patients covered by the program. Altenburg projects those subsidies would total a minimum of $19,000 under his plan, and likely more. “I assumed the lowest possible subsidy,” he said. He also notes that the on-call staff won’t be paid additionally for ambulance runs, and estimates that this will offset the higher pay afforded volunteer drivers, saving about $14,000 annually. “Volunteer” drivers are currently paid $25 an hour for ambulance runs, while Altenburg’s latest plan calls for paying emergency medical technicians, or EMTs, $11 an hour.

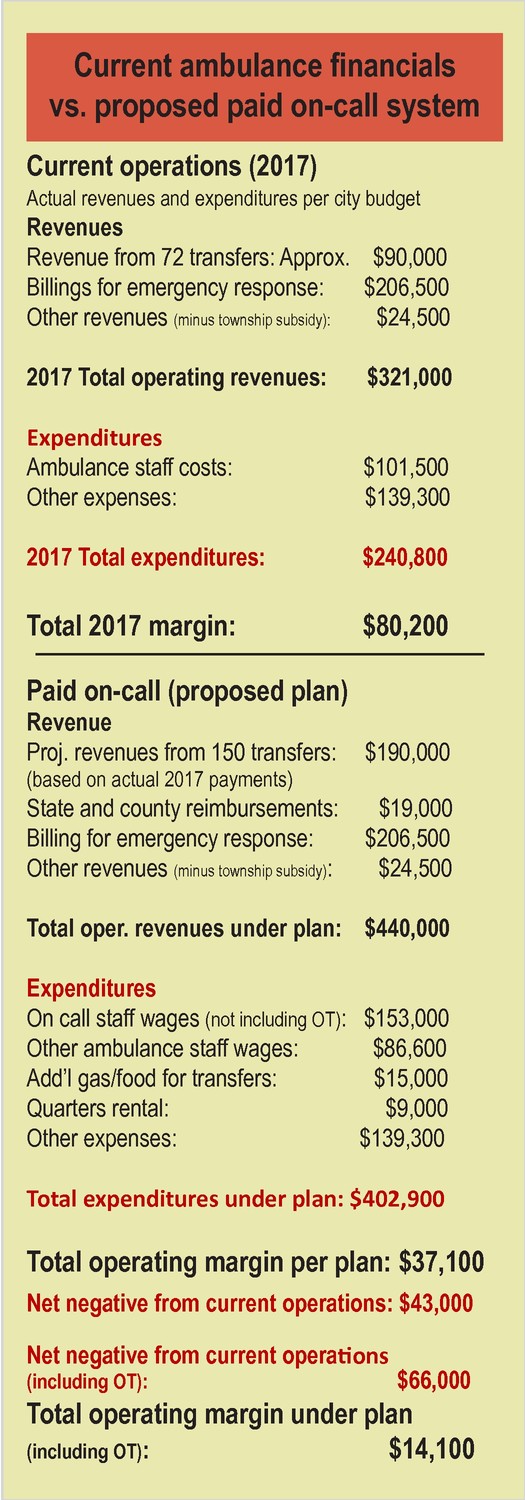

Even with the additional revenue and savings, a Timberjay analysis (see sidebar) concludes that the paid on-call staffing would reduce the ambulance service’s margins by $43,000, or $66,000 if overtime costs are considered.

Under its current staffing model, the ambulance service took in a total of $343,515 in 2017, according to the most recent numbers provided by the city, although $22,675 of that is township support earmarked for ambulance purchases. That leaves operating income of $320,840. Total expenditures through 2017 totaled $240,827, according to the latest city budget numbers, leaving an operating surplus of $80,013.

While Altenburg’s staffing proposal would likely still leave a surplus, it could well be reduced by as much as 82 percent.

That’s a different scenario from the one presented to the council last year when Altenburg originally offered his plan. Altenburg said he was satisfied that the council approved the plan and that members knew what they were voting for. But when asked if members of the council were aware that his plan would, in fact, likely not pay for itself as he had suggested, Altenburg responded: “I know for sure that two understand that,” he said. “Actually, three of them do,” said Keith, who was also in the interview. “I was going to say three but I couldn’t remember for sure,” replied Altenburg.

“Why wouldn’t the whole council know that?” this reporter asked.

“Because what difference does it make?” responded Altenburg. “Not a single one of them asked ‘Are we going to profit less money?’”

Moments later, Altenburg again suggested his plan would not impact the service’s budget. “The plan has been approved and I’m confident if executed the way I have laid it out that it will pay for itself, and that the ambulance isn’t going to lose money.”

A question

of mission

Altenburg said the mission of the ambulance service is to provide emergency patient care, not to make money. “The issue is patient care— that is our mission,” said Altenburg. “As long as you are still generating a net plus at the end of the day, that’s all that matters.”

Altenburg argues that the service will benefit by having staff on-call five days a week, arguing that it will provide a faster response time for patients.

That may well be true in many cases, but not in all instances. Altenburg’s plan could increase response time for some local patients if it diverts available staff to non-emergency transfers more frequently. That is what happened one evening in mid-February, while one of the Tower service’s two ambulances was on a transfer to a psychiatric facility in Thief River Falls. A mutual aid call from Ely took the service’s second ambulance up the road, which meant no ambulance was available when an emergency medical call came in from Fortune Bay. Tower had to request mutual aid for that call from the Cook Ambulance.

“That’s why we have mutual aid,” noted Altenburg.

Mutual aid does provide a backstop for such situations, but relying on it can significantly increase response time, depending on the location of the patient and the distance of travel for a mutual aid responder.

That’s why most ambulance services try to limit the number of transfers they’ll accept. “You can do the transfer, but you always have to have a crew available to respond to an emergency,” said Bob Norlen, field services supervisor for the state of Minnesota’s Northeast EMS region. “It would be tough to explain if someone died of a cardiac arrest while you were on a transfer.”

While most other services accept less than half of the transfer requests they receive, Altenburg suggests that Tower can do substantially more. His estimate of 150 transfers would be equal to two-thirds of the requests the service received in 2017, and he argues the service may be able to do even more, in order to generate more revenue. Which raises the question of whether the quest for transferw revenue could potentially overshadow the broader mission of emergency patient care.