Support the Timberjay by making a donation.

Could “greening” of the steel sector bring a new boom to the Range?

REGIONAL— The greening of the steel industry will bring big changes to Minnesota’s Iron Range, and those changes could be beneficial or devastating to the region’s economy, …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Attention subscribers

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, below, or purchase a new subscription.

Please log in to continue |

Could “greening” of the steel sector bring a new boom to the Range?

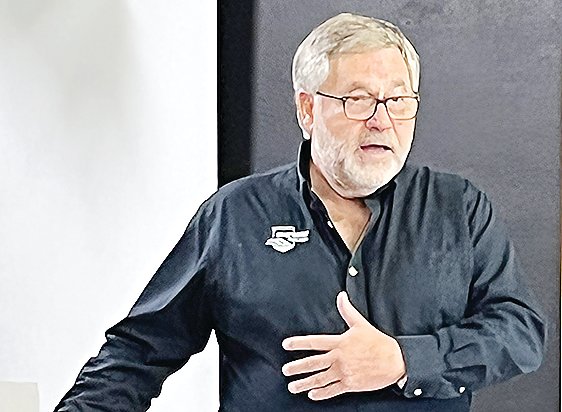

REGIONAL— The greening of the steel industry will bring big changes to Minnesota’s Iron Range, and those changes could be beneficial or devastating to the region’s economy, depending on how the industry and state leaders chart a future that’s in rapid flux. That was the message from Jeff Hanson, a partner in Babbitt-based Clearwater BioLogics, who has worked closely with the region’s iron mining industry for years on solutions to sulfate pollution.

Hanson offered his views during a regular meeting of the Ely Climate Group last week and he provided a mostly optimistic vision about the prospects for major improvements in the greenhouse footprint of the steel industry— and the resulting economic opportunity for the Iron Range.

Hanson noted that the steel industry currently accounts for a whopping nine percent of all greenhouse gas emissions, making it the second most-polluting economic sector, behind only transportation. But he said the industry is undergoing a rapid transition away from traditional blast furnaces, which contribute the bulk of the carbon emissions from the sector, toward electric arc furnaces that can be more easily powered with green energy, and that transition is happening quickly in the United States.

Already, about 78 percent of steel produced in the U.S. is coming from arc furnaces and as that percentages continues to increase, Hanson noted that the need for the traditional taconite pellets, which are designed as feedstock for blast furnaces, will fade away. “If blast furnaces are on their way out, what are the prospects for the Iron Range?” Hanson asked rhetorically. “Not very good,” he added.

Hanson’s comments came in the same week that Gov. Tim Walz was on the Iron Range to meet with U.S. Steel officials at the Keetac mine, where U.S. Steel is investing $150 million to produce direct reduced-grade pellets. Cleveland Cliffs already produces such pellets on the Iron Range, which can become feedstock for DRI processing plants, currently located in the lower Midwest.

While economics is the primary driver of the change in steel production, Hanson said the need to reduce greenhouse emissions is prompting a related shift to the use of green energy in steel production and that the Iron Range could enhance its importance to the industry, and increase mining-related employment in the region, by taking steps in that direction.

Hanson’s view is hardly out of the mainstream. The European Union has already established several demonstration projects that will utilize a combination of green electricity and hydrogen produced through renewable sources of energy to produce steel with little or no greenhouse-contributing carbon emissions.

While clean hydrogen has long been a dream for engineers mapping out the energy transition away from fossil fuels, the relatively high cost of producing clean hydrogen (electrolyzed from water using renewable sources of power like hydro, solar, or wind) has limited its acceptance in the marketplace to date.

But Hanson and many in the investment community believe that will change quickly thanks in part to the recently passed Inflation Reduction Act. “It’s investing $400 billion in clean energy, mostly focused on hydrogen,” notes Hanson.

Currently, most hydrogen is produced to make fertilizer or in oil refining and virtually all of it is produced through the burning of fossil fuels, mostly natural gas. Hydrogen is created through electrolysis, which breaks the bonds between the hydrogen and oxygen atoms that make up water, a process that requires an enormous amount of electricity to produce hydrogen at a scale that would be needed in the current economy.

According to energy experts, a transition to hydrogen could provide a viable alternative fuel for much of the transportation sector, including heavy trucking, container shipping, and airliners, all of which could be powered with hydrogen-based fuel cells. It would also replace natural gas used in producing DRI.

A shift to hydrogen produced through traditional sources of power provides little advantage, however, in terms of carbon emissions, which is why the production of clean hydrogen has been a kind of Holy Grail for years.

Producing hydrogen from renewable sources of power requires no new technology in theory, but as with most new economic sectors, ramping up to scale and increasing efficiency can require significant investment. Hanson sees the Inflation Reduction Act, which has now enacted a ten-year production tax credit as high as $3 per kilogram for hydrogen produced entirely with clean energy, as a boon that will likely push clean hydrogen production into overdrive.

Many others agree.

In a Sept. 27 story, Utility Dive, a website that focuses on the utility industry, reports that the new tax credits could well make hydrogen a very widely produced commodity almost instantly.

“Everyone is looking at putting hundreds of megawatt-scale facilities on the ground, immediately,” said Margaret Campbell, director of business development for green hydrogen at Engie North America, as quoted by Utility Dive a news website focused on the utility industry. “The demand is urgent, immediate, and enormous.”

The hydrogen industry had already been targeting production costs of $2 per kg by 2030 according to Utility Dive, so a $3 per kg tax credit would effectively make hydrogen free or nearly so in many areas.

Potential for the Iron Range

As Hanson sees it, the Iron Range will need to complete its ongoing shift to the production of DRI-grade pellets to maintain any relevance in an industry that will, by necessity, be making the shift to carbon-reduced and eventually carbon-free production.

“One thing we know about climate change is that if we keep doing what we’re doing we’re doomed,” said Hanson.

Failing to make the transition could doom the region’s mining economy much sooner than the planet, he said. Yet, by investing in the technology that will drive the industry in the future, he said Minnesota and the industry could create the kind of economic boom that the region hasn’t seen since the dawn of taconite.

Hanson said the region currently has some, but not all, of the ingredients needed to make the transition. An ongoing source of iron ore is key but leveraging that resource to actually bring steel production to the region will take new investments in clean energy and energy storage, Hanson believes. Currently, Hanson notes that DRI-grade pellets produced on the Range are shipped to DRI processors in Ohio. Hanson notes that most of the steel industry is located in the lower Midwest due to its proximity to coal reserves, which was critical to traditional steel production. As the importance of coal in the process is reduced or eliminated, Hanson said it creates the opportunity to relocate steel production closer to the source of iron.

He said a more energy efficient process would create DRI and feed it directly into an arc furnace, eliminating much of the energy cost of transporting and reheating the pellets.

To fully transition to green steel production would require replacing natural gas with clean hydrogen and utilizing electricity from renewable sources. While the region currently has some renewable power sources, Hanson said it’s not sufficient to meet the industry demand, but he said investments in energy storage, which could take advantage of some of the region’s unique attributes— like an abundance of mine pits lakes— to create energy storage capacity.

Hanson said Minnesota, with leadership and investment, could engineer a major transition on the Iron Range that could bring major environmental benefits and huge numbers of jobs. “As you look into the crystal ball, this could be a big, big deal for northern Minnesota,” he said.