Support the Timberjay by making a donation.

High price for clean water

High price for clean water

REGIONAL— The St. Louis County Board has thrown its backing to a state bonding request for a $24 million project to address a problem that supporters can’t show even exists. At issue is a …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Attention subscribers

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, or purchase a new subscription.

If you are a current print subscriber, you can set up a free website account and connect your subscription to it by clicking here.

If you are a digital subscriber with an active, online-only subscription then you already have an account here. Just reset your password if you've not yet logged in to your account on this new site.

Otherwise, click here to view your options for subscribing.

Please log in to continue |

High price for clean water

High price for clean water

REGIONAL— The St. Louis County Board has thrown its backing to a state bonding request for a $24 million project to address a problem that supporters can’t show even exists.

At issue is a proposal by the Voyageurs National Park Clean Water Joint Powers Board, which goes by the cumbersome acronym VNPCWJPB, to build a centralized wastewater collection and treatment system to serve a total of 81 sites along Ash River, a tributary to Lake Kabetogama.

It’s not the first such project the VNPCWJPB has undertaken in recent years, and it’s not the first time some of the organization’s decisions have been questioned for their extraordinarily high cost and questionable benefit.

From the beginning, the VNPCWJPB and SEH, the engineering firm that has driven much of the process, has focused on the development of mostly centralized wastewater treatment systems built around pockets of commercial and residential development along the edges of Voyageurs National Park, including at Crane Lake, Lake Kabetogama, Ash River, and Rainy Lake. As Minnesota’s only national park, the VNPCWJPB has cited the “need” to clean up the park’s major lakes as reason enough to support truly enormous expenditures of public funds.

The problem, according to the project’s engineers, are individual septic systems at lakeshore cabins and resorts, many of which they claim are failing or no longer compliant, allowing them to leak pollutants, mostly phosphorus, into area lakes. Phosphorus is frequently a limiting nutrient in Minnesota lakes, so the addition of phosphorus can lead to more frequent and more intense algae blooms.

Evidence lacking

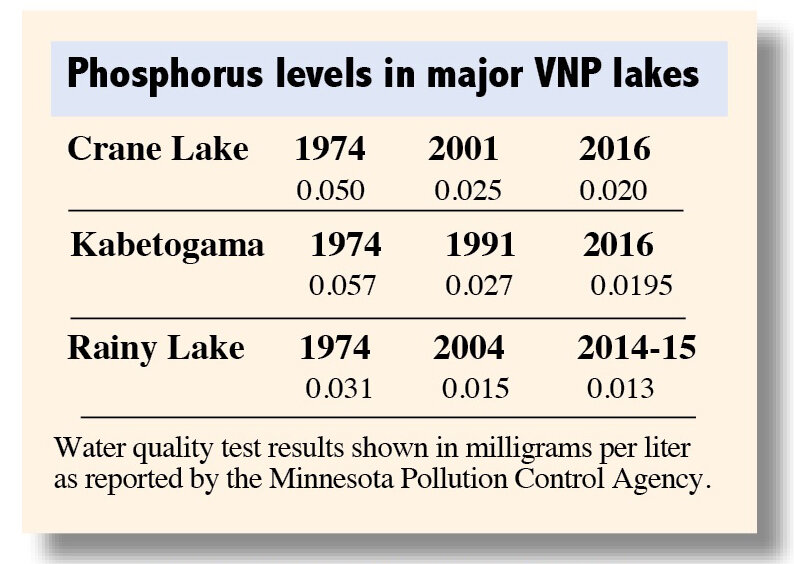

Yet, while the VNPCWJPB’s mission appears to be worthwhile, the board has actually done little to document the problems it claims to be addressing. Far from declining water quality, the relatively limited testing data available from the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency shows that phosphorus levels on major lakes within the park have been declining for decades. That’s due, in part, to stricter regulations surrounding the design and permitting of individual septic systems as well as the phaseout of phosphorus in products like laundry detergent.

Back in the 1970s, testing at Crane Lake and Lake Kabetogama yielded phosphorus levels averaging at or above 0.05 milligrams per liter (mg/l). Subsequent testing demonstrated continuing declines in phosphorus levels. By 1991, testing on Kabetogama found that phosphorus levels had fallen to an average of 0.0265 mg/l and that had fallen even further, to just 0.0195 mg/l as of the most recent testing in 2014-15.

Both Crane and Rainy lakes, experienced similar trends of declining phosphorus levels over the same time frame.

Nor has the VNPCWJPB documented that any septic systems in their service area are actually discharging inadequately treated wastewater into surface waters. The master plan for the Ash River project claims that 23 systems along the river are either “non-compliant” or “probably non-compliant,” although that in itself is not evidence a system is actually polluting. Another 15 systems were rated as “maybe non-compliant” or “may be compliant.”

The SEH engineers who drafted the master plan acknowledge that it based its determinations on reviews of permit paperwork and other county records, rather than onsite inspections that could confirm whether any of the systems was actually polluting.

Individual septic systems, when operating properly, should have no discharge of pollutants to surface waters. That’s according to Sara Heger, a University of Minnesota researcher and associate professor with the university’s Water Resources Center, who works with homeowners and communities to plan onsite sewage treatment solutions. “At the end of the day, the wastewater coming out of a septic system is cleaner that what comes out of a treatment plant,” Heger said. “There is this whole idea that a treatment plant is the best option. But a lot of time for the environment, it’s not better to be hooked up. The output from a well-maintained septic system is zero.”

Extraordinary costs

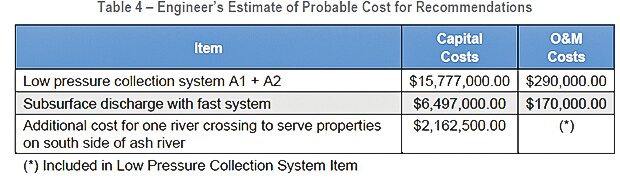

The Ash River project is currently estimated at $24 million, although given recent inflationary trends in construction, the price could well go far above that. The same engineer who is behind the cost estimates at Ash River had recently projected the cost of a new drinking water treatment facility in Tower at $5.5 million, while earlier this month the project’s lone bid came in at $9.1 million, which has put that project in limbo.

To raise $24 million, supporters of the Ash River project are seeking $7 million in congressionally directed spending for the project, along with an additional $7 million in state bonding. Grants from several other sources could bring in another $8 million in mostly state dollars, while an anticipated $2 million loan from the Public Facilities Authority would round out the funding.

The VNPCWJPB, in a recent resolution, claim that they’ve already received commitments from Third District Sen. Grant Hauschild and Rep. Roger Skraba to advocate for state bonding dollars for the project. Hauschild said he met with members of the VNPCWJPB and SEH recently to discuss the project, but acknowledged he had not read the master plan and was unfamiliar with the details of the proposal. He said given the high number of projects that lawmakers are asked to back every year, he has to rely on local elected officials to undertake that kind of due diligence. “This was vetted as a county priority. I guess I don’t really know why they are making this such a priority, if it’s so costly,” he said.

Given the relatively small number of cabins or homes involved, the cost of the project is astounding. While the master plan cites 81 cabins currently in the area they propose to serve, roughly half of them have septic systems that are compliant or may be compliant, or use holding tanks or outhouses, which typically don’t pollute. Many of the cabins are relatively small and are used only seasonally or on weekends and generate very little wastewater.

Depending on how one calculates it, the project’s cost per cabin served ranges from $296,000-$470,500.

“That’s insane,” said Heger, when informed of the project’s price tag. “There’s no one in their right mind who would say that’s a good idea— except people who don’t have to pay for it.”

The cost of construction is just part of the overall price tag. The project’s master plan projects an annual operating expense of $460,000, and it’s not clear where the money to cover those costs will come from. County commissioner Paul McDonald, who chairs the VNPCWJPB, said the board’s goal is to keep the monthly charge to users to about $100. But even if the owners of all 81 cabins in the coverage area are assessed a $100 monthly fee, that would generate just $8,100 a month. With an anticipated operating cost of $38,333 a month, that leaves an enormous funding gap. Covering that gap through fees to users would require a monthly charge of nearly $475 for the owners of each of the 81 affected cabins, or more than $5,000 a year.

McDonald said that the project would likely not proceed with construction without adequate funding that allows for affordable rates for the users. “I believe the goal for the Ash River District is in the $100/month range per EDU. This rate is similar to the rates for the existing systems at Island View, Kabetogema, and Crane Lake.”

Does it make sense?

Local officials in the area have come under fire in the past for pushing expensive centralized wastewater treatment systems. When Crane Lake officials faced criticism and threats of lawsuits from residents over a similar plan there, the board overseeing the project reached out to Heger, who agreed to consult on the project. Heger said she eventually felt that she was brought in more to provide political cover than advice the Crane Lake officials intended to rely upon.

Heger had argued at the time for a different model, one which relied on individual septic systems or cluster systems in some cases, with a sewer district that manages the systems and pays for maintenance and eventual replacement as needed. Other lake communities in Minnesota, such as Otter Tail County, have adopted a similar approach, providing protection for lakes at a small fraction of upfront capital and subsequent operating and maintenance costs than the model proposed by the VNPCWJPB.

When asked about alternatives, McDonald said the members of the joint powers board were familiar with the Otter Tail service district, and noted that the Crane Lake Sewer District operates a hybrid system, with a centralized pipe system that serves portions of the community with a managed septic system program elsewhere on the lake.

“A managed ISTS system is not a recommended solution for the Ash River District as many of the lots in the service area are too small for properly sized ISTS systems,” said McDonald, in comments on the issue he offered earlier this year. “There are also many issues in that area with bedrock and high groundwater levels.”

St. Louis County continues to permit septic systems for lake homes and cabins in northern parts of the county, using mound systems that are designed for areas with shallow soils and high water tables.

Questionable claims

Adding to the concern about the Ash River project are claims made by the VNPCWJPB. A resolution approved by the board this past December, which was submitted to Congress and other potential funders claims that the board’s efforts have had “a very positive impact on the waters of Voyageurs National Park and the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness.” Yet, the board has made no data available publicly that documents an improvement in water quality in the park as a result of their efforts. What’s more, none of the waters within the BWCAW are impacted by the VNPCWJPB’s work since the wilderness area is located upstream of the area served by the board. County officials, when asked about that discrepancy, acknowledged an “administrative error.”

In addition, the project’s master plan appears to make claims that either aren’t factual or are highly exaggerated. The plan categorizes a large portion of the southeast shore of the Ash River as “high-density residential,” and proposes extending a sewer line under the river to connect cabins along that stretch of shoreline. In fact, the plan indicates a total of 17 properties along that approximately one mile of water-access shoreline, many of which include very small and rustic cabins assessed at less than $50,000, and with annual property tax bills of around $1,000.

Is money driving the process?

A 2022 report produced by SEH for the VNPCWJPB pegs the combined cost of their proposals for Ash River, Crane Lake, Kabetogama Township, and Rainy Lake at an eye-popping $104.9 million. The report further notes that a 25-percent engineering fee is built into that figure, which means that full implementation of the plan would be expected to net SEH about $26 million.

“That is the biggest issue, that engineers work on a percentage of the project,” said Heger.

Supporters of the Ash River proposal note that the MPCA approved their proposal back in June 2022, but the agency focuses its review on whether or not the plan will protect water quality, not whether it’s cost-effective.

Heger said that’s where the plan falls short. “I’m not saying that what they’re proposing won’t work. At the end of the day, it will protect the environment. But will it do so in the mostly economical and sustainable way? The answer is no.”

Heger notes that the ultimate goal of any such proposal should be to remove as much phosphorus from wastewater discharges as possible for every dollar spent. “That’s what we should care about. Not lining anybody’s pocket.”

Heger, an advocate of onsite wastewater treatment, said engineering firms have a built-in aversion to wastewater treatment programs designed around installing and maintaining well-designed individual or clustered septic systems, an approach that is typically far less costly than the methods that SEH has consistently pushed with the VNPCWJPB. But she said many engineering firms don’t have septic system designers on staff and so don’t recommend solutions dominated by the use of such systems. In St. Louis County, non-engineers are routinely certified to work as septic system designers and their typical fees are modest by comparison with a large engineering firm.

“Going back to the engineering firms,” said Heger, “lower cost simply isn’t to their advantage.”

In the end, Heger said it should come down to the effective use of public funds. She notes the state has only so much funding available for clean water projects, so when funds aren’t spent cost-effectively, it’s a setback for the overall goal of cleaner water in Minnesota lakes. “As a taxpayer, that’s what I care about.”

The Timberjay submitted questions last week to the St. Louis County Administrator seeking documentation of the need. County officials replied right at presstime and offered little additional information.