Support the Timberjay by making a donation.

MONARCH SUMMER

Monarch numbers have spiked in the North Country. That seems like good news.

While the long-term prospects for the monarch butterfly remain in doubt, there is evidence that the individual efforts of people who care about this remarkable insect are making a difference. The …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Attention subscribers

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, or purchase a new subscription.

If you are a current print subscriber, you can set up a free website account and connect your subscription to it by clicking here.

If you are a digital subscriber with an active, online-only subscription then you already have an account here. Just reset your password if you've not yet logged in to your account on this new site.

Otherwise, click here to view your options for subscribing.

Please log in to continue |

MONARCH SUMMER

Monarch numbers have spiked in the North Country. That seems like good news.

While the long-term prospects for the monarch butterfly remain in doubt, there is evidence that the individual efforts of people who care about this remarkable insect are making a difference.

The good news is that monarch butterflies and their larvae are being seen in huge numbers in many parts of the North Country this year.

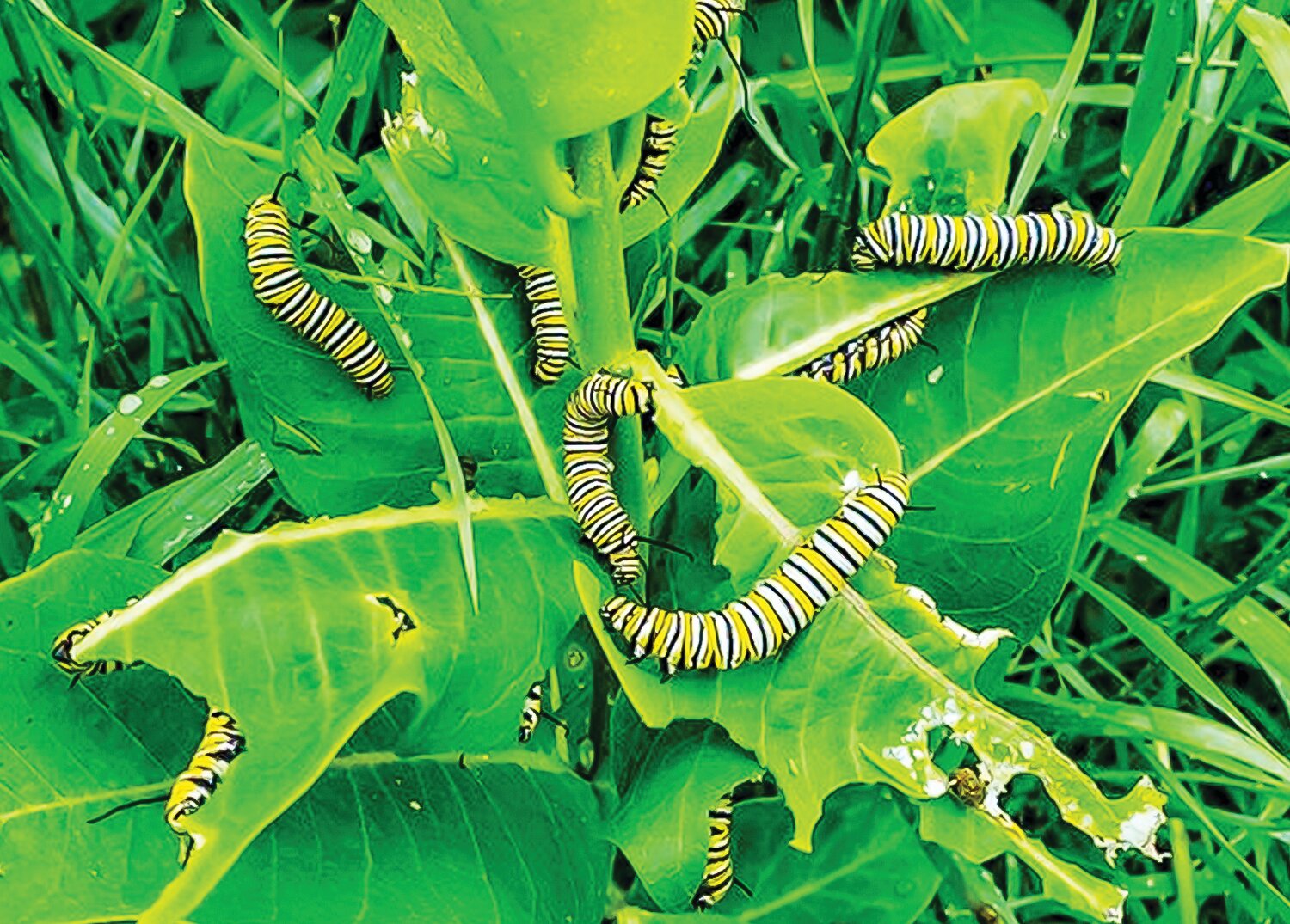

“It’s just been unbelievable,” said Kelly Dahl, of Linden Grove, who has seen some of the volunteer milkweed plants near his high tunnel chewed right down to the stalk by monarch caterpillars, which are readily identifiable by their unique yellow, black, and white striping.

He’s actually gathered and moved hundreds of the larvae in recent days to a larger patch of milkweed nearby, so they have enough food to make it to the pupal stage and to be less visible to potential predators.

Dahl said he’s never seen a year with so many monarch caterpillars and it’s a hopeful sign after last year, when the butterflies and their larvae were relatively hard to find in the region.

Chip Hanson is an Ely veterinarian but he’s also a close observer of the natural world. He agrees with Dahl that this year has seen a remarkable resurgence in monarch numbers— at least here in northeastern Minnesota. “One day, I counted 135 [monarch] caterpillars in my garden,” Hanson said. “I’ve never had anything close to that before.”

Monarch numbers can vary significantly from year-to-year in part because they’re subject to the vagaries of wind currents. This year, the winds seem to have brought them to the North Country in exceptional numbers. That could be a fluke, or a sign that the species might be doing better than a decade ago, when numbers plummeted, raising public concern that the population was finally succumbing to a series of stressors.

It’s well known that the monarch population has been in trouble, so much so that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is considering protection under the Endangered Species Act.

Habitat loss is one of the biggest factors in the decline of the species in recent years, but most experts on the species see climate change as the biggest long-term threat. While there’s little individuals can do by themselves to reduce the effects of climate change, that’s not the case with habitat destruction. Individuals and organizations throughout North America have taken it upon themselves to grow milkweed, the plant upon which the monarch life cycle depends. In gardens all across the country, particularly in the Midwest— the heart of monarch breeding territory— individuals have planted patches of milkweed in hopes of sustaining the population. It’s a classic example of individual collective action and it may be making a difference.

Cathy Anderson, of Tower, is one who has turned her attention to the monarch. Just this week, Anderson was tending her roughly 225 square-foot patch of dense milkweed, which she planted just a few years ago in her small backyard. In the right conditions, milkweed will thrive and spread quickly, as Anderson’s patch, which she grew from just two original plants, attests.

Around noon earlier this week, her patch was alive with monarch butterflies flitting about. She also maintains small, screened enclosures on her back patio, where she carefully places the monarch caterpillars she finds along with milkweed plants that she places inside. In the protection of the enclosures, the monarch caterpillars stand a much better chance of making it to their adult stage. Inside her enclosures were dozens of monarch caterpillars as well as chrysalises.

Anderson monitors the enclosures regularly and releases the butterflies once they have emerged from their chrysalis.

Thousands of Americans are doing the same thing in an effort that is loosely organized at best, but is inspired by a shared awe for this iconic North American species.

Can it be enough to save this species from extinction? It certainly offers hope, as long as humans continue to interact meaningfully with the natural world, an open question in an age when so many youth seem lost in a virtual world.

On a broader scale, policy changes could make a difference. The widespread adoption of herbicide resistant crops as well as federal policies to encourage the production of renewable fuels, like ethanol, have contributed to a dramatic decline of milkweed in agricultural regions. Farmers, who used to take advantage of programs like the Conservation Reserve Program, or CRP, which used to provide millions of acres for milkweed, have since put those acres back into commodity production have eliminated vast amounts of monarch habitat.

The small patches now being grown in gardens all across the country are making a difference, but can they replace the truly vast amounts of milkweed lost in recent years? It’s not clear, but one thing’s for sure: The future of monarch depends on it.