Support the Timberjay by making a donation.

RANCH RESOLUTION?

It’s said good fences make good neighbors. That may even include wolves for this remote cattle ranch north of Orr

SHEEP RANCH ROAD— For years, cattle rancher Wes Johnson has lost several head of cattle every year to wolves. His 1,500-acre operation, located about 15 miles north of Orr, is a rarity here at …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Attention subscribers

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, or purchase a new subscription.

If you are a current print subscriber, you can set up a free website account and connect your subscription to it by clicking here.

If you are a digital subscriber with an active, online-only subscription then you already have an account here. Just reset your password if you've not yet logged in to your account on this new site.

Otherwise, click here to view your options for subscribing.

Please log in to continue |

RANCH RESOLUTION?

It’s said good fences make good neighbors. That may even include wolves for this remote cattle ranch north of Orr

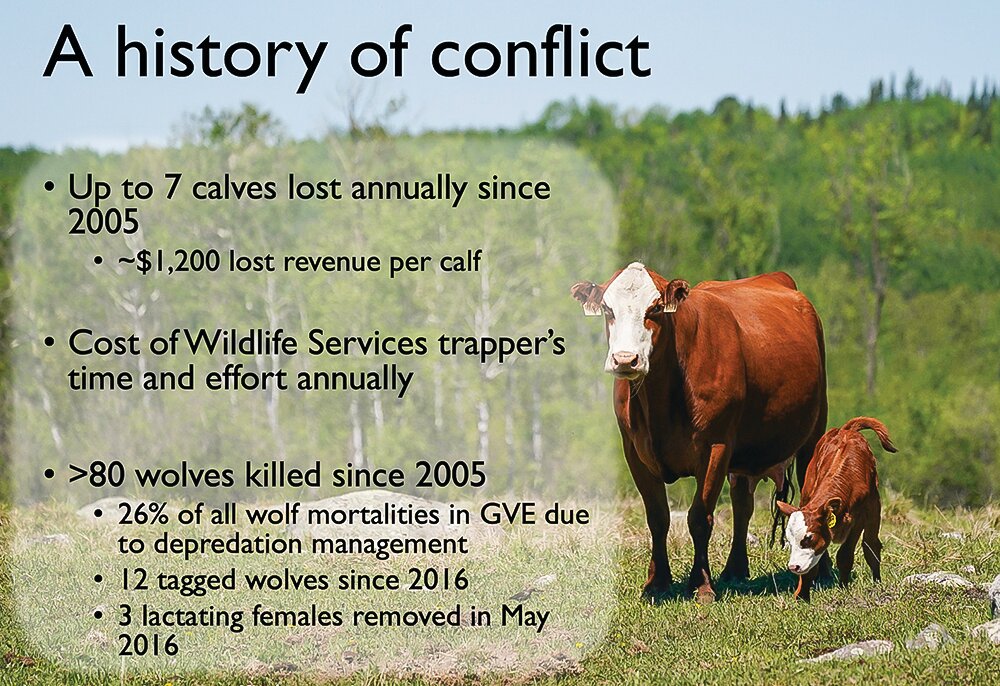

SHEEP RANCH ROAD— For years, cattle rancher Wes Johnson has lost several head of cattle every year to wolves. His 1,500-acre operation, located about 15 miles north of Orr, is a rarity here at the southern edge of the boreal forest, where ranches are few and often confined to 100 acres or less.

Johnson’s ranch isn’t just large for the region, it is uniquely located in the heart of the densest population of gray wolves in North America, according to Austin Homkes, a researcher with the Voyageurs Wolf Project. Four separate wolf packs border the sprawling ranch, all of which have used Johnson’s cattle, mostly his calves, as an occasional food source for decades.

In other words, it’s ground zero in the longstanding battle between ranchers and wolves. It’s also now the site of an experiment that could provide a model for substantially reducing, or even eliminating, the loss of cattle in some cases to Minnesota’s top wild predator.

A costly problem

Johnson’s losses have been significant over the years, although he doesn’t have an exact number of how many calves he’s lost to wolves. “I’ve probably lost over a hundred head at least,” he said. “At over a grand apiece that adds up.” And while he is reimbursed for lost cattle when he can find a carcass, often the entire calf simply goes missing, which means no reimbursement. It’s the same story when calves or cows are injured in wolf attacks, even if they later have to be put down.

But this spring, at a time when his cows are calving and wolves are normally taking advantage of an easy meal, Johnson said all is quiet on the ranch, thanks to the installation of a wolf-proof metal fence, completed last year, which is keeping the wolves at bay.

“It’s going great, so far,” said Johnson, who was riding the calving grounds on a mild, sunny day this past week. “The cows are calm and quiet.”

The fence is a joint experiment hatched two years ago by stakeholders who all had something to gain from a permanent solution to Johnson’s wolf problem. Both state and federal agencies, including the Minnesota Department of Agriculture and U.S. Wildlife Services, were expending taxpayer resources each year. The state dollars went for reimbursement for lost cattle, and since 2005 the reimbursement fund had paid out about $150,000 for losses at Johnson’s ranch. Meanwhile, Wildlife Services paid for federal trappers to trap and kill wolves on the ranch.

Since 2005, federal trappers have trapped and killed at least 80 wolves from Johnson’s ranch, or about ten percent of the local wolf population every year. That not only affected Johnson’s operations, it impacted the Voyageurs Wolf Project since the project’s study area includes Johnson’s ranch and the four wolf packs that surround it. Since 2016, federal trappers had caught and killed 12 of the project’s GPS-collared wolves. The losses of valuable research animals had created some occasional friction between the researchers and the federal trappers. Those frictions came to a head two years ago in a tense meeting between officials with Wildlife Services and researchers. Lead researcher Tom Gable said the federal officials were concerned that their trapping of wolves for radio-collaring was “educating” wolves about traps, making it harder to catch problem animals on the ranch.

Gable countered, noting that Wildlife Services was killing collared wolves that he could prove weren’t involved in depredation on the ranch. When the representatives from Wildlife Services suggested he move his study, Gable refused, but suggested erecting a fence as a possible solution.

The timing appeared to be ideal. All involved recognized that the longstanding pattern of addressing wolf depredation through trapping hadn’t solved the problem on the ranch and they were looking for another way of addressing the issue. It was an unusual alignment of interests, one that brought wolf advocacy groups like the Humane Society of the U.S., which strongly opposes the killing of wolves, together with a longtime rancher, federal trappers, and wildlife researchers, to construct and study the impact of the fence.

“The key to the project was collaboration,” said Homkes, noting that all parties had an interest in a solution to the ongoing problem. “In the end, we all worked together for a common goal.”

Gable agreed and gave Johnson much of the credit for making it work. “Wes is a reasonable guy. He doesn’t want the conflict with the wolves. He just doesn’t want to lose his calves. He’s has been super jazzed about the project. He’s been really active in making this a success.”

The project was a major undertaking, noted Homkes, who discussed the project during a recent webinar on the topic. First, crews had to clear miles of brush around the existing barbed wire fence located along the perimeter of the ranch, to allow for installation of the woven metal fencing. Then, they had to install the 49-inch high fencing, along with a two-foot apron laid on the ground just outside the fence to prevent wolves from digging underneath.

It wasn’t the first time Johnson had explored non-lethal ways to address his wolf problem. He’d tried protection animals, like dogs and donkeys. He’d tried regular patrols of his borders to discourage wolf activity. He’d tried electric fences, but the wolves quickly learned to evade them.

So, when the idea of the permanent metal fence was broached, Johnson was willing to give it a try— and it has proven to be the ideal location for such an experiment. Given the involvement of the Voyageurs Wolf Project, which deploys trail cameras and uses GPS collars on wolves throughout its study area, including the packs surrounding the ranch, it’s possible not only to measure the reduction in wolf depredation but to see in real time how wolves are responding to the presence of the fence, including when they find ways to evade it.

Creek beds and uneven terrain are among the challenges to keeping wolves off the ranch. Low water can let wolves slip underneath in a dry creek bed. Last year’s high water conditions tore out a section of the fence where it crossed a local creek. When heavy snow drifted into the creek bed, wolves were able to step over the fence. A fallen tree can flatten the fence anywhere along the seven and a half mile perimeter of the ranch, allowing another point of entry.

Once one wolf discovers an entry point, others quickly follow, but the GPS collars on some of the members of the pack, or trail cameras deployed along portions of the fence, help pinpoint trouble spots that need maintenance.

Those GPS collars, which regularly ping the locations of the wolves, used to show wolves from the four surrounding packs routinely used the ranch in their day-to-day hunting and other movements. But since the installation of the fence, those same GPS locations show that the fence has become a nearly impenetrable barrier, save for an occasional issue, to the wolves. And that’s making making Johnson’s life as a rancher a lot less stressful.

The new fence wasn’t cheap to build. Materials alone ran about $70,000, according to Homkes, with a total price tag of about $100,000. But a number of agencies and nonprofits with an interest in the experiment helped fund some of it. Staff from the research project, Wildlife Services, and Johnson’s operation all pitched in with labor to make it happen. But given the potential to reduce Johnson’s losses, save tax dollars on reimbursements and trapping, and reduce the toll on the ongoing wolf research in the area, Johnson figures it’s a good investment. “In the long run it’s going to pay for itself,” he said.

Another tool in

the toolbox

John Hart says he’s heartened, but not surprised, by the effectiveness of the fence. Hart is the district supervisor of Wildlife Services, based in Grand Rapids and he sees the fence as a sensible approach in some instances. “It’s another tool in the toolbox,” he said, noting that it’s a good fit for ranches that are isolated so the wolves don’t simply go elsewhere. “It’s not a silver bullet for every depredation issue,” Hart notes. “It has to be isolated from other ranches, otherwise, you’re kind of blowing the leaves into your neighbors’ yard.”

While the fence at the Johnson’s ranch is perfectly located for an experiment of this kind, Hart said he was involved in the fencing of another cattle ranch, near Effie, which had experienced significant wolf depredation as well. That fence, installed in 2020, has been equally effective. “Knock on wood, but we haven’t had a loss since.”

While it’s an expensive approach, Hart agrees it’s probably worth it for ranches that have experienced significant losses on a regular basis, given that it can reduce losses by the producer as well as save tax dollars. “We haven’t done a cost-benefit analysis yet, but think there will be a payoff in the long run,” he said.