Support the Timberjay by making a donation.

“We knew this was coming”

Bat numbers plummeting in Arrowhead

SUPERIOR NATIONAL FOREST— Deep in the woods of northeastern Minnesota, biologists are confirming a bat apocalypse. The region’s once-robust populations of little brown and northern longed-eared bats, both members of bat genus Myotis, appear to have declined dramatically just since last year.

For the biologists, it’s not a surprise— it’s a sign that the deadly fungal agent that causes whitenose syndrome has taken a firm hold on what had been the region’s two most common bat species.

Using mist nets at night, U.S. Forest Service biologists began assessing bat populations on the national forest in 2013, to gather baseline data in anticipation of the spread of the deadly bat disease to the region, and to learn more about the kinds of habitat that bats use. Researchers first detected the deadly fungus, known as P. destructans, at the Soudan Underground Mine State Park in 2013. The mine is the state’s largest known bat hibernaculum and it serves as the winter refuge for much of the area’s bat population. Park staff found the first signs of significant mortality at the mine in 2016, but mortality spiked dramatically this past winter, with a survey suggesting bat mortality of about 70 percent.

Based on the findings of researchers in the field this summer, the mine survey may have, if anything, undercounted the extent of the population collapse.

Up until this year, the researchers working on the bat census netted an average of 8-10 northern long-eared or little brown bats per night, according to U.S. Forest Service biologist Tim Catton. This year, he said, they’ve averaged just under two bats per night, although many nights they’ve come up empty.

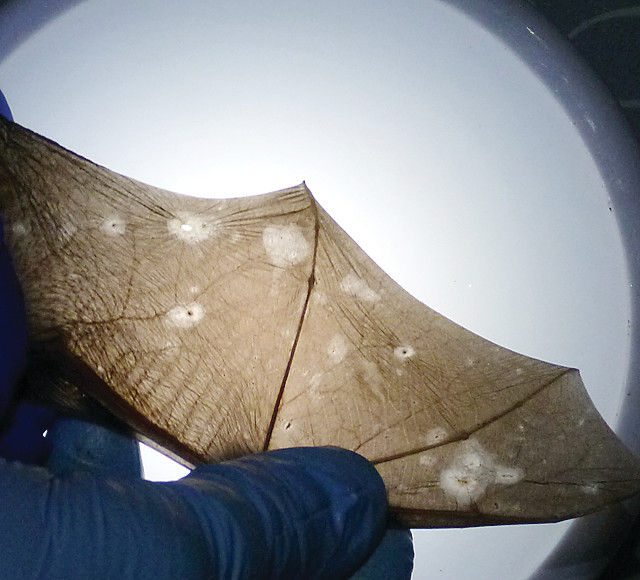

“This year is really the fall-off,” said Catton, noting that the research had begun to notice spots on the wings of bats they netted last year, which is a hallmark of P. destructans infection. “We knew this was coming, but hadn’t seen the real mortality until this year. I would imagine our netting success will drop to zero next year.” Indeed, that prediction has already come to pass for northern long-eared bats. “We’re not seeing any of them,” said Catton.

While the population collapse is not a surprise, Catton said the research so far has yielded some unexpected results. “We’re catching very few females,” he said, noting that the sex ratio is way off from their usual results. That could be a statistical fluke, or evidence that whitenose syndrome is hitting female bats the hardest. Catton said most adult females would be carrying a developing embryo during hibernation, which likely puts more of an energy stress on females than males. Whitenose syndrome typically kills bats by disrupting their hibernation and forcing them to expend critical energy reserves at a time when insects are not available, leading to eventual starvation.

If the disease is disproportionately killing female bats, that’s likely to make population recovery much more difficult. It’s also hindering one important element of the current research, which is to locate maternal roosts where bats raise their young. When the researchers do capture a female bat, they glue a tiny transmitter to its back, which allows biologist to find the roosting tree that the bat is using. Bats typically prefer dead or dying trees with cracks, crevices, or exfoliating bark, which create the kinds of tight, protected spaces that bats prefer, particularly to raise their young. Researchers want to know what trees bats prefer, as well as the kind of surrounding habitat that is most conducive to bat roosting.

Such information is key to understanding what, if anything, land managers can do to help the bat species that are highly susceptible to whitenose syndrome to survive, and aid in an eventual recovery of their populations. “The states of Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan are working together on a habitat conservation plan designed to help the bats by conserving their habitat during land management activities,” said Rich Baker, threatened and endangered species coordinator for the Minnesota DNR. The state is also seeking an incidental take permit from the federal Fish and Wildlife Service, and obtaining the permit requires development of a habitat conservation plan. Fish and Wildlife added the northern long-eared bat to the federal threatened species list last year, in anticipation of the devastation from whitenose syndrome.

Developing a habitat conservation plan requires understanding bat behavior and how they use their forest habitat, and biologists have had little data upon which to draw in the past.

“We just don’t know a lot about bats in Minnesota, where they hibernate and where they go,” said Catton. “It took something like this for us to start really studying them.”

Baker notes that it isn’t clear how much bats will benefit from habitat protection, given the source of the problem. “We have to acknowledge that the problem is not a lack of roost sites, it’s whitenose syndrome in their hibernacula,” he said. “But having said that, we recognize that reproduction is what keeps populations going, and that happens in the forests in the summer. Roost trees may not be limiting right now, but we don’t want them to ever get there.”

Bats doing better elsewhere

Catton and his fellow researchers will be moving over to the Chippewa National Forest later this month, and he said he’ll be interested to see if the population decline is similar as they have documented in the northeast. While whitenose syndrome has devastated bat populations in the Soudan Mine, it’s not clear how many of the little brown and northern long-eared bats living outside northeastern Minnesota hibernate in the mine.

Other parts of Minnesota, notes Baker, have yet to see the kind of falloff being experienced in the Arrowhead. In fact, bat populations appear to be up slightly in southern and central parts of the state, based on mist net surveys in those areas this summer. Baker notes that some bat hibernacula in the state still show no sign of P. destructans, much less symptoms of whitenose syndrome.

And even where P. destructans has appeared, the impact is not always predictable. Researchers detected the fungus at Mystery Cave in southeastern Minnesota the same year they found it at Soudan. But while Soudan has experienced a huge die-off, the bat population at Mystery Cave shows little evidence of change, at least so far.

“We think it’s just a matter of time,” said Baker.