Support the Timberjay by making a donation.

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

When it comes to the “popple,” there’s more than you might expect

What’s in a name? When it comes to the common name, “popple,” it can mean one of three distinct tree species in northern Minnesota. My parents grew up in northwestern Minnesota so …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Attention subscribers

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, below, or purchase a new subscription.

Please log in to continue |

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

When it comes to the “popple,” there’s more than you might expect

What’s in a name? When it comes to the common name, “popple,” it can mean one of three distinct tree species in northern Minnesota.

My parents grew up in northwestern Minnesota so they were well-acquainted with the term popple, since that’s what everyone called these fast-growing trees with the light-colored bark and the leaves that wave in the slightest breeze. I learned that term from my parents until my naturalist days, when I was expected to leave generic, common names behind and be able to identify the individual species we tend to lump together under the term “popple.”

So how do you tell the popples apart? It’s pretty easy when you know the distinguishing features of our three common popples, all members of the genus Populus: the quaking aspen, the big-toothed aspen, and the balsam poplar.

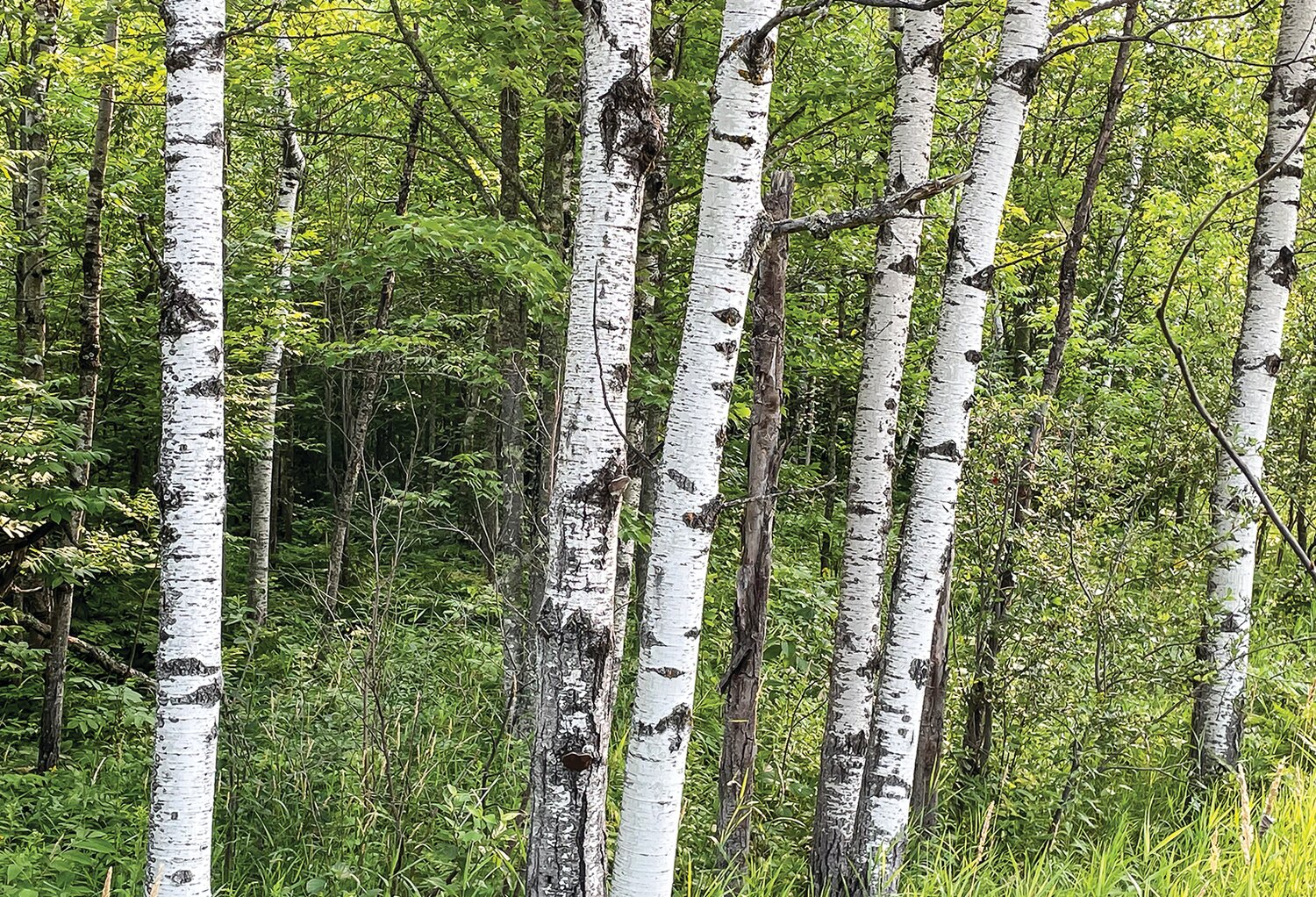

Of these three, the quaking aspen, Populus tremuloides is by far the most common, at least in our portion of northern Minnesota. It’s actually the most widespread tree species in North America, with a range stretching from Newfoundland to westernmost Alaska, encompassing the northern tier of U.S. states and higher elevations in the Rockies as far south as Arizona and New Mexico.

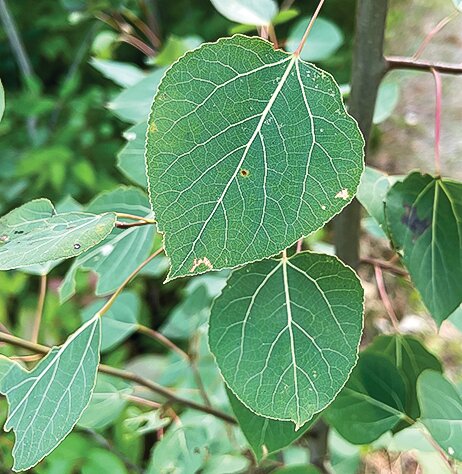

It’s recognized by its relatively smooth, whitish-green bark and by its generally roundish, finely toothed leaf that comes to a fine point. The quaking aspen is often mistaken for paper birch, which is certainly possible from a distance, but up close, the two species are easy to distinguish. Paper birch bark peels off, like paper, while the aspen bark does not.

The quaking aspen got its name because their leaf stem is exceedingly narrow, which makes the leaves flutter in almost any breeze.

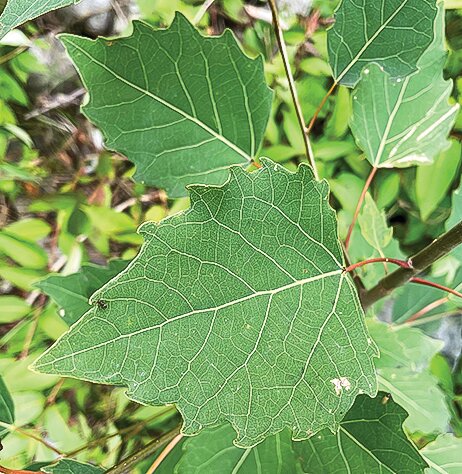

It’s a trait that the species shares with its close relative, the big-toothed aspen, Populus grandidentata, which has a much more limited range, running from the Canadian Maritimes to Minnesota, centered around the Great Lakes. It’s easy to confuse this species with its more common and widespread cousin, but there are a few good distinguishing characteristics that can help you tell the difference.

The first is the bark, which is more of an orangish-green than the whitish green of the quaking aspen. And as its name suggests, the big-toothed aspen will give itself away if you can get a look at their leaves, which are prominently toothed.

Two other characteristics are worth noting. This tree’s new leaves of spring are very frost sensitive, much like a black ash, so they are among the last of our native trees to leaf out in the spring, often appearing dead right up until June. And when those new leaves do start to develop, they are noticeably silver in color for the first week or two before shifting to their summer green.

The quaking aspen, by contrast, is one of the earliest trees in the region to leaf out, occasionally popping as early as April in response to an early warm spell.

The third species colloquially dubbed popple in our area is the balsam poplar, or Populus balsamifera. This is a tree with other names as well, including Balm of Gilead for its resinous leaves, which have a strong and distinctive scent. Balm of Gilead has been shortened to “Bam” among most foresters and loggers in our region, which just goes to show that the common names of many species are frequently fluid as well as imprecise.

The balsam poplar can be distinguished from other popple in our area by its coarser bark, by its noticeable scent, and by its more pointed leaves that are thicker than its aspen cousins and definitely more resinous.

Balsam poplar generally grows better on damper sites and is not typically found in the drier rocky locations which tend to be favored by big-toothed aspen.

You typically don’t find these three species growing intermixed in a stand— and that’s because the poplars grow in stands that are generally clones of each other, which are all interconnected through an often-extensive root system that can be hundreds or even thousands of years old and can extend for an acre or more. When you cut an aspen tree, you’re essentially pruning a branch of the original clone, and the organism responds by quickly sending up shoots to replace it.

As you spend time outdoors in the coming weeks, take a closer look at the “popple” around you and see if you can spot the differences I’ve mentioned here. And with autumn soon approaching, you can use the changes in leaf color to help distinguish these species. The quaking aspen is famous for its distinctly golden leaves, which hit their peak in the first week of October. The big-toothed aspen are more variable, ranging in color from gold to peach to red.

If you enjoy fall color, the balsam poplar will be a disappointment. Their leaves often drop early having turned brown with, at best, a hint of yellow.